BLOG

—

For Earth Day’s 50th Birthday, Celebrate the Gift of Perspective

Normally, I celebrate Earth Day by participating in a community service project with my kids and Woolpert colleagues. This year is a quandary: What to do for this strange and special 50th Earth Day? It seems right this anniversary year to celebrate by reflecting on our progress, appreciating the unique lessons of today and forging ahead as designers of the future we envision.

We often use the first Earth Day, April 22, 1970, as a line in the sand, marking when Americans raised our environmental consciousness and officially recognized the impact we have on our ecosystem, as well as its impact on us. In truth, Earth Day is just one milestone in a slow American cultural shift toward acknowledging our integration with and dependency upon natural resources, away from the false ideas that we either dominate nature or that nature is too big and wild for us to affect.

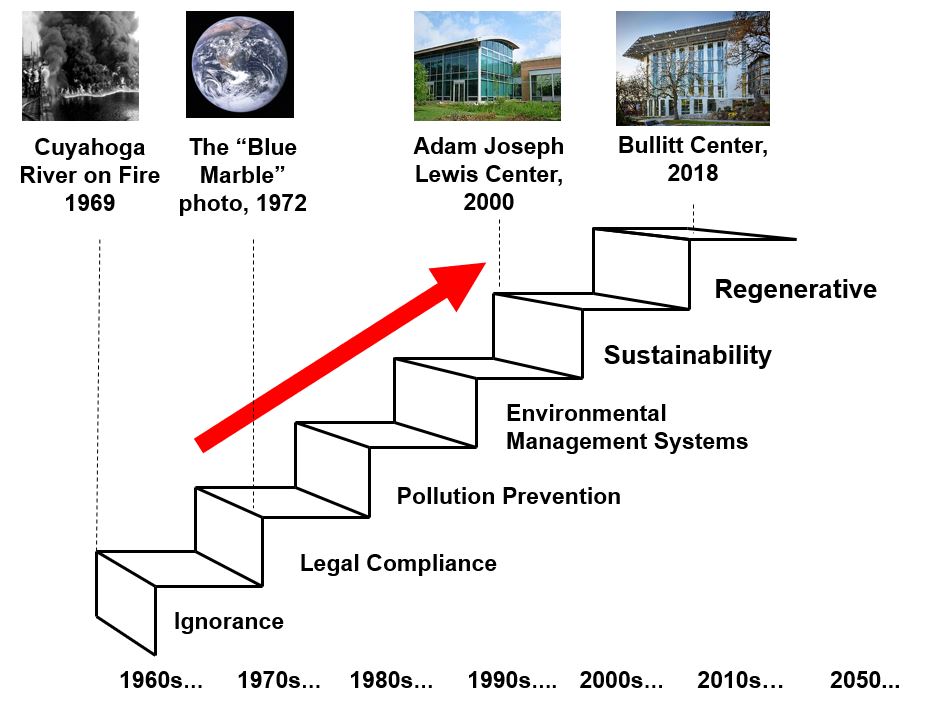

The embarrassing visage of the Cuyahoga River on fire is credited with sparking the establishment of Earth Day in 1970. The heavily polluted river had caught fire at least a dozen times before, but news of this fire was shared nationally amid rising accounts of oil spills and smog, effectively fueling the demand for action. Congress established the Environmental Protection Agency in January 1970, and Earth Day was born three months later.

In 1972, the crew of Apollo 17 gave us the famous “blue marble” image of the Earth, helping us see ourselves as passengers on a singular, beautiful spacecraft. When your paradigm shifts to living on that blue marble in space, you see the fallacy in throwing anything away, since there is no “away” in a closed system.

In the years that immediately followed that first Earth Day, every major piece of environmental legislation was reactionary. Something terrible would happen—like toxic waste bubbling through the soil at Love Canal in New York or the lethal nighttime gas leak in Bhopal, India, that killed thousands, for example—and then we would pass a law. Many early laws focused on doling out pollution by “permitting” it. Sadly, we still apply for permits on many projects, often without thinking that we’re applying for the right to pollute on behalf of our clients.

Then came a milestone most have never heard of—the passage of the Pollution Prevention Act of 1990. It declared a radical idea that “pollution should be prevented or reduced at the source” instead of regulating it. With no regulatory teeth, its practical effect was limited; but this was a key step in a new, proactive direction.

As a sustainable designer, my core belief is that the lives and growth of our species can be a healthy and regenerative contributor to nature’s cycles—just like any other species. Our societal challenge is to redesign and re-engineer our products to support a high quality of life for “all the children of all species for all time” by mimicking natural processes and cycling materials, energy and water safely over and over again (quote courtesy of William McDonough, author of the beautiful Address to Woods Hole Symposium).

One-way material flows—extracting materials, processing them into products using large amounts of energy and water, often mixing materials so they contaminate each other and can’t be reused, and then throwing those materials into landfills or incinerators after one or even several uses—simply can’t persist. The general public’s current fixation on plastics (like the current public enemy, the plastic straw) is a big piece of this broader material reinvention challenge. My fellow designers, what better celebration of Earth Day than to (re)commit to eliminating the very concept of pollution? We can design buildings and infrastructure that serve human needs and purposes, but also follow nature’s rules.

The Lewis Environmental Center at Oberlin College in Ohio was a bellwether building for sustainable design when it opened in 2000. It generates its own power and treats its own wastewater with now 20-year-old technology. I have not looked at buildings the same way since visiting the Lewis Center. Sustainable design throws out the old question of “How can we be less bad?” from an environmental perspective and asks, “How can we be good?” (again, full credit to McDonough for these words). Regenerative design is the next natural step, which asks, “How can our buildings and communities restore the ecosystem services we’ve damaged?” The Bullitt Center in Seattle is the brightest example today in what designers are capable of: a living building.

Our journey does not end with the 50th Earth Day celebration. It’s a mile marker on the road to making human influence on the planet regenerative. The crisis we’re experiencing now can teach us helpful lessons, if we let it. The first lesson is that nature humbles us. It is bigger and more powerful than each of us. We can be taken at any moment by a tiny virus or a powerful storm. Nature does not respect human constructs such as social classes, education or affluence. We can bring that sense of humility, rather than dominance, to nature in our everyday actions. The second lesson we can take from this is to appreciate how we are living with far less pollution and how we all are able to enjoy noticeably better air quality. Can these changes be sustained post-COVID19?

Join me in celebrating this 50th Earth Day by reflecting upon our progress and committing to our journey ahead.

Nadja Turek

Nadja Turek, PE, LEED AP B+DC, EN, WELL AP, GGP, is a civil engineer and sustainable design expert. The former faculty member at the University of Dayton and the Air Force Institute of Technology, is a sought-after consultant, teacher and speaker. For her industry leadership, Nadja was invested as a Fellow by the Society of American Military Engineers in 2017.