BLOG

—

Landscape Architecture: The Shifting Sands of Resilience in the 21st Century

Peering down a length of the High Line in the vibrant Chelsea neighborhood in New York City, it is easy to recognize what resilient design looks like. The formerly abandoned elevated rail line has been converted into a park complete with walking paths, shops and gardens.

Design professionals and landscape architects (LAs) in particular continue to play an increasing role in fostering and adhering to resilient design principles. LAs not only play a key role in creating memorable places and landscapes that are functional and beautiful, but we continue to define what resilient design means in the 21st century.

According to the Resilient Design Institute, resilient design is “the capacity to adapt to changing conditions and to maintain or regain functionality and vitality in the face of stress or disturbance. It is the capacity to bounce back after a disturbance or interruption. From Katrina to Sandy, California drought to Mississippi flooding, resilience is both response and action.” As our climate changes, so too have the attitudes and strategies of designers. The design of resilient spaces is innate to the profession of landscape architecture.

While the profession is sometimes confused with horticulture or lawn care professionals, a landscape architect’s extensive training moves swiftly into other avenues, including resilient design. Coursework on materials and structures, land analysis and site planning, construction documentation, horticulture, environmental and natural systems—as well as the study of people, community and place—all contribute to our education. It is this wide breadth of coursework and professional experience that make LAs leaders in resilient design.

From McMansions to Urban Retrofits

Toward the end of the 20th century and into the 21st century, there was a major paradigm shift in where people were choosing to live. The push to develop “raw” and agricultural land into sprawling suburban communities began to wane, while developers began looking closer at city cores where abandoned and often neglected properties sat vacant. This shift gained traction, especially on the heels of the 2007-2008 financial collapse.

People who had sought “McMansions” in far-flung suburban communities were now looking for smaller places closer to city centers where commutes were shorter and cultural destinations and services were closer to home. Urban cores saw neglected, forgotten and deteriorated properties transform from masses of concrete and asphalt into metropolitan oases for many to enjoy. This allowed for multiple resources to be conserved by leaving land undeveloped, decreasing commutes and tapping into existing municipal utilities.

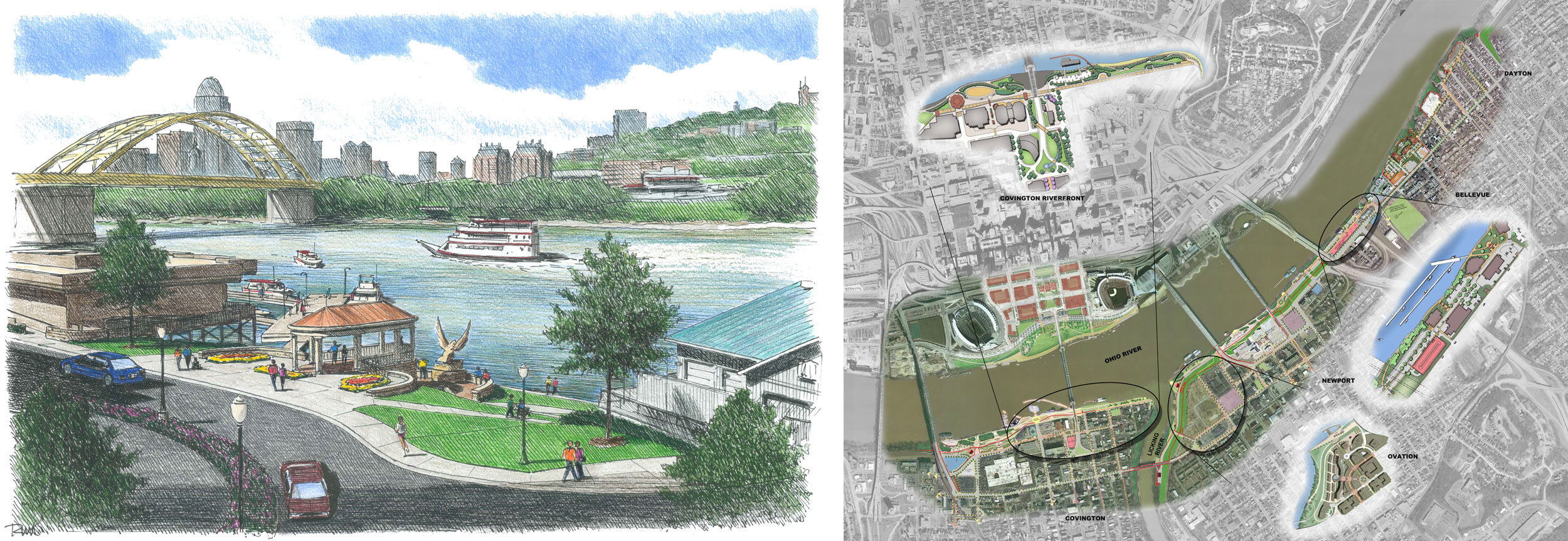

As a result of this shift, riverfronts—such as Louisville’s along the banks of the Ohio River—saw ambitious plans for revitalization blossom. Gone are the shipping wharves and parking areas, and in their place are public open spaces for large gatherings and intimate spaces for use in smaller public gatherings like family picnics. Louisville’s Waterfront Park incorporates many obvious resilient features, including native plantings and local materials. More subtle features that add to the resilience of this park are pervious areas for the Ohio River to expand and contract; multimodal transportation, including paths and a pedestrian bridge that crosses the river into Indiana; and a strengthened connection between the benefits of the riverfront and the residents of the city.

Cities across the U.S. are reinventing how they view infrastructure projects, transitioning from gray structures of pipes and concrete to green structures like rain gardens that treat and slow stormwater along roadway rights-of-way. Rain gardens are not only beautiful amenities, they are functional in absorbing pollutants and stormwater runoff from hard surfaces such as sidewalks or driveways and decrease the volume and velocity of water that enters stormwater systems and waterways.

While these retrofits seem to be simple ways to aid in stormwater infiltration, their acceptance has been slow but steady—due in large part to the consistent progress of LAs. These resilient, environmentally beneficial features typically use native plants, allow for groundwater recharge and promote local wildlife, while easing pressure on aging urban stormwater structures worldwide.

Creative Solutions at Home and Abroad

Countries often regarded as being ahead of the curve in resilience are becoming more imaginative in creating and retrofitting spaces that are not only resilient in nature but align with climatic change. For example, Denmark is seeing higher rainfall totals and increased flooding along its coastlines, with the North Sea to the west and Baltic Sea to the east. With the help of LAs, the town of Roskilde found a creative way to harness and control stormwater during extreme events. Its Rabalder Park, a genius public works creation, not only serves as a stormwater conveyance feature, but also functions as a skatepark when dry.

LAs are pushing the boundaries with several initiatives that promote the design of resilient landscapes. The National Park Service has programs that further the integration of resilience in cultural landscape management. For instance, Gateway Arch National Park in St. Louis recently saw a nearly $400 million makeover that focused on resilience. The updated design features grassy meadows, numerous native plant species in extensive gardens and additional pervious surfaces. The design connects visitors and residents to the park with multiuse paths and a land bridge that crosses over a once-impassable interstate, allowing access to its historically significant Old Courthouse.

LAs also have played a pivotal role in the Sustainable SITES Initiative, which is a set of comprehensive, voluntary guidelines and rating system that assesses the sustainable design, construction and maintenance of landscapes. The SITES Rating System, which was produced by the Green Business Certification Inc., is based upon substantive measures developed as an interdisciplinary collaboration that includes the American Society of Landscape Architects. The SITES designation is the standard for the creation of resilient and sustainable development projects, including the Earvin “Magic” Johnson Recreation Area in Los Angeles, AT&T Discovery District in Dallas and the Minneapolis Convention Center Plaza.

The 21st century has seen no shortage of innovative thinking and design. LAs continue to blaze trails in what sustainable and resilient development means and how it’s best integrated into design strategies. The LAs at Woolpert aim to continue this trend and introduce more forward-thinking projects to the world around us.

Stay tuned for the third and final installment of this blog series, which will focus on projects that exemplify these ideals.

Jason Thomas

Jason Thomas, PLA, is a landscape architect at Woolpert who works with multidisciplinary teams to find creative, environmentally friendly and sustainable solutions for a variety of clients. Thomas is involved with planning and executing projects that include a shoreline restoration in Newport News, Va., and feasibility studies for various schools in coastal Virginia. He is president of the Virginia Chapter of the American Society of Landscape Architects.