Corporate hangars are often pre-engineered metal buildings that don’t always conform to manufacturers’ standard sizes. This Indianapolis Executive Airport facility provides second-floor elevator access for offices; houses ventilation for two exterior 12,000-gallon fuel tanks and 40,000 gallons of underground storage for fire protection; and features an all-glass, 120-by-28-foot hydraulic lift door. The exterior matches the client’s other buildings across the U.S.

BLOG

—

Not All Corporate Hangars Are Created Equal

But they all must address the same design questions to develop a productive relationship with the owner and satisfy the client.

Driven by growth in U.S. GDP and corporate profits, more and more companies are buying, maintaining and piloting their own fleet of planes. According to the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA), sales of turbine-powered jets are projected to grow 2% a year to 2039; turbojet sales, 2.2% a year. In 2018 alone, business jet deliveries rose 17%.

Companies need a place to store and care for these assets, so the demand for corporate hangars is also growing. But corporate hangars aren’t like other commercial buildings. Yes, they need lobbies, storage, conference rooms, kitchens, bathrooms and parking. They also must be accessible, incorporate fire suppression and tie into existing utilities. But that’s where the similarities end.

Business jets run on unleaded kerosene or a naphtha-kerosene blend, which means they’re essentially bombs with wings. To minimize the potential for crashes during ground navigation and provide unobstructed views for airborne pilots, FAA guidelines strictly regulate hangar height as well as location relative to taxiways, runways, other buildings and roads. Obtaining FAA and airport board approval on hangar location and orientation is the critical first step in constructing a hangar. In addition, local authorities often have their own zoning regulations, utility connection requirements and permitting prerequisites.

Hangars also have unique internal spaces, such as pilot and flight prep areas, and they almost always have outdoor fuel tanks and equipment right next to the building. As a result, designers spend more time educating aviation clients than, say, developers of office parks and warehouses.

Want to be in the know for an upcoming hangar project? Here are five things most people don’t know about corporate hangars.

1. The plan starts with the plane.

Business jets are growing, with tail heights of some new models pushing 27 feet. Because plane size and number influence hangar size and configuration, the mix of current and future aircraft is foundational for design discussions. What model(s) does the client own? Does the client expect to expand its fleet? How many and how large? The answers to these questions drive hangar and door size, the first cost estimation.

2. What happens in the hangar?

Hangars can be used to store and/or maintain planes. Not surprisingly, code complexity increases with size and function. Storage-only hangars are generally smaller than their maintenance counterparts, but they still require clients and designers to address apron size and plane parking/tie downs. Maintenance hangars need dedicated work spaces and storage for equipment like tugs and lifts.

3. Get the planes in, get the planes out.

Hangar doors can slide from side to side like barn doors, lift vertically or fold horizontally like garage doors. Each mechanism has pros and cons related to hangar function, door opening size and location. Whatever the final choice, the door is a costly component and must meet the owner’s functional requirements vis-à-vis maintenance.

4. You can’t fight fires with water.

Jet fuel burns at 800° to 1500°F. While a fire that hot isn’t likely to melt the steel many hangars are made of, it won’t be extinguished by water, either. In fact, water is more likely to spread the fire.

States base their fire protection specifications on International Building Code (IBC) occupancy uses and building types. Once the hangar’s internal area surpasses 40,000 square feet and/or door height reaches 28 feet, the IBC and National Fire Protection Association require foam/water fire suppression. Depending on state and local requirements, foam storage and dispersal systems can have significant impact on the design—and cost!

5. Location, location, location.

A company can house its fleet at any of 2,903 general aviation (GA) airports across the nation (GA airports don’t support military or, usually, commercial flights). Each one charges rent for the land on which a hangar is located; fuel; and, depending on local laws, property tax on fleet value.

A no-frills, 5,000-to-6,000-square-foot hangar costs $750,000 to $1 million; hangars 12,000 square feet and larger can range from $2 million to more than $50 million depending on the client’s needs. Add those figures to facility operating costs, and a client’s making a significant investment.

So, in addition to guiding site development and facility design, part of my job is counseling clients on where to house their fleets. Factoring in all these considerations is a delicate balance, but one that with the proper foresight and insight, enables me and my colleagues to efficiently complete cost-effective projects.

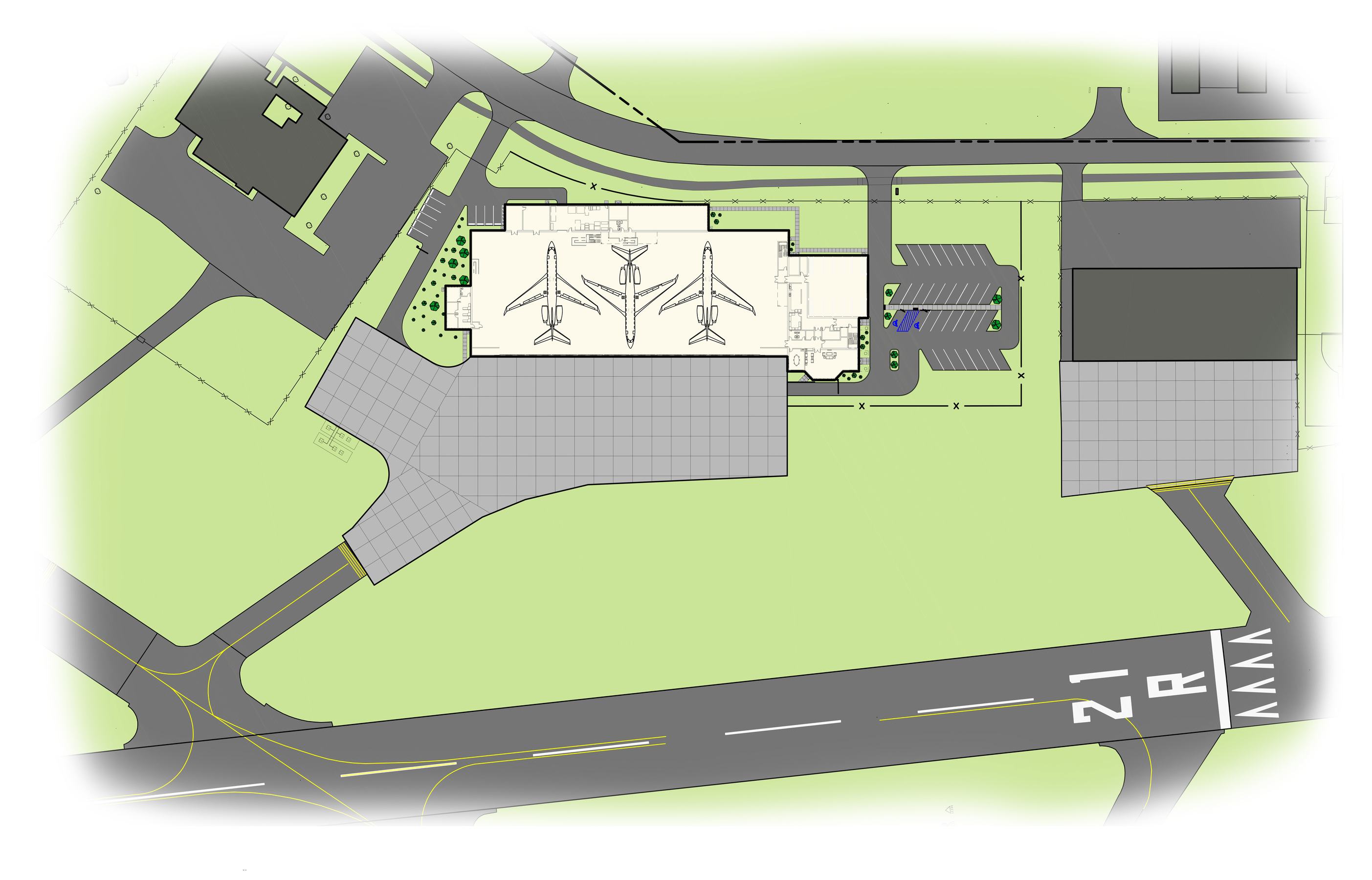

This is the proposed hangar design for Cincinnati-based insurance and investments company at historic Lunken Airport in downtown Cincinnati.